In July 2024, five student-built capsules endured the scorching heat of re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere as part of the second Kentucky Re-Entry Probe Experiment (KREPE-2). Scientists are now analyzing data from the KREPE-2 experiments, which could advance the development of heat shields that protect spacecraft when they return to Earth.

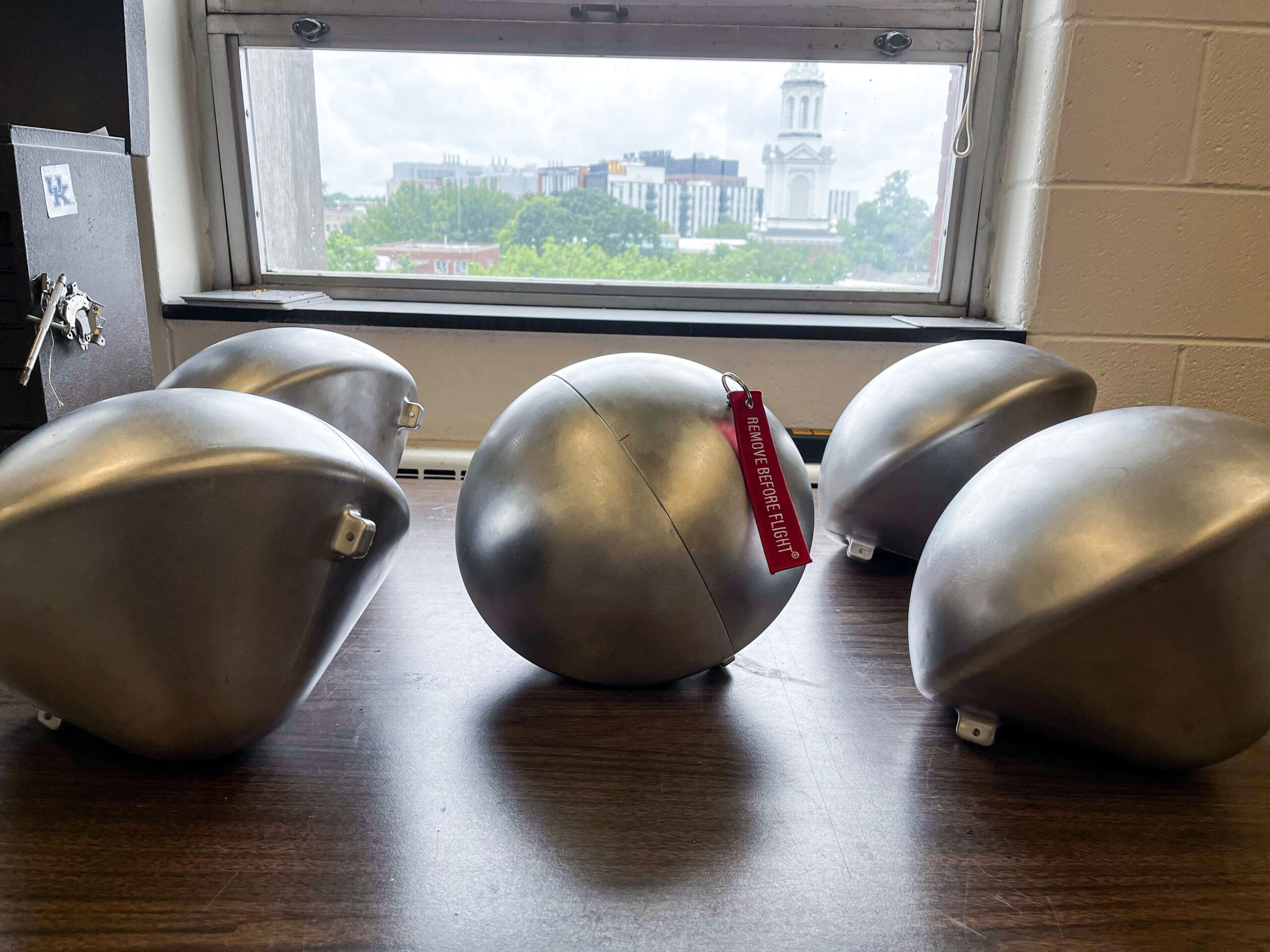

The mission was designed to test a variety of heat shield prototypes under authentic re-entry conditions to see how they would perform. These experimental capsules, which were built by students at the University of Kentucky and funded by NASA’s established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR) within NASA’s Office of STEM Engagement, all survived more than 4,000 degrees Fahrenheit during descent.

The football-sized capsules also successfully transmitted valuable data through the Iridium satellite network during their fiery journey. The collection of information they provided is currently being analyzed for consideration in the current and future design of the spacecraft and to be refined into models for future experiments.

“These data — and the instruments used to acquire the data — help NASA design and evaluate the performance of current and new spacecraft that transport crew and cargo to and from space,” said Stan Bouslog, senior expert of the thermal protection system discipline at NASA’s Johnson. Space Center in Houston, who served as the agency’s technical monitor for the project.

Taking the plunge: Communicating through a fiery descent

“The only way to ‘fly test’ a thermal protection system is to expose it to actual hypersonic flight through an atmosphere,” Bouslog said.

The self-contained capsules launched aboard an uncrewed Northrop Grumman Cygnus spacecraft in January 2024 along with other cargo destined for the International Space Station. The cargo ship undocked from the space station on July 12 as the orbital laboratory flew over the southern Atlantic Ocean. As the Cygnus spacecraft began its planned disintegration during reentry, the KREPE-2 capsules detected a signal—a temperature increase or acceleration—to begin recording data and were released from the vehicle. At that point, they were traveling at a speed of about 16,000 miles per hour at an altitude of about 180,000 feet.

The team of University of Kentucky students and counselors watched and waited to learn how the capsules fared.

As the capsules descended through the atmosphere, a group watched from aboard a plane flying near the Cook Islands in the South Pacific Ocean, where they tracked the return of the Cygnus spacecraft. The flight was organized in partnership with the University of Southern Queensland in Toowoomba, Queensland, Australia and the University of Stuttgart in Stuttgart, Germany. Alexandre Martin, professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the University of Kentucky and principal investigator for the experiment, was on that flight.

“We flew close to the reentry path to take science measurements,” Martin said, adding that they used multiple cameras and spectrometers to observe the reentry. “We now have a much better understanding of the Cygnus vehicle breakup event, and thus the release of the capsules.”

Meanwhile, members of the University of Kentucky’s Hypersonic Institute had gathered at the university to watch the KREPE-2 data arrive via email. All five successfully communicated their flight conditions as they dropped to Earth.

“It will take time to extract the data and analyze it,” Martin said. “But the big achievement was that each capsule sent data.”

University of Kentucky student team members have begun analyzing the data to digitally reconstruct the flight environment at the time of transmission, providing key insights for future computer modeling and heat shield design.

Building on Student Success

The mission builds on the achievements of KREPE-1, which took place in December 2022. In that experiment, two capsules recorded temperature measurements as they re-entered Earth’s atmosphere and transmitted that data back to Earth.

The extensive data collected during KREPE-2’s re-entry includes measurements of heat shielding, such as temperature, as well as flight data including pressure, acceleration and angular velocity. The team also successfully tested a spectrometer that provided spectral data of the shock wave in front of a capsule.

“KREPE-1 was really about showing that we could do it,” Martin said. “For KREPE-2, we wanted to fully instrument the capsules and really see what we could learn.”

KREPE-3 is currently set to be developed in 2026.

The ongoing project has provided valuable opportunities for the University of Kentucky student team, from undergraduates to doctoral students, to contribute to the innovation of spaceflight technology.

“This effort has been done entirely by students: the fabrication, running the simulations, handling all the NASA reviews and doing all the testing,” Martin said. “We’re there supervising, of course, but it’s always the students who make these missions possible.”

Related links: